Carlos Sandoval was riding the New York subway when he read an editorial in the New York Times commemorating the case, Hernández v. Texas. The case began in 1951 in the small town of Edna, where Pedro “Pete” Hernández murdered his boss in the parking lot of a cantina. At the behest of Hernández’s mother, San Antonio attorneys Gus Garcia and Carlos Cadena took the case. On January 11, 1954, they stood before the nine justices of the Supreme Court where they argued for the full protection of Mexican Americans under the 14th Amendment.

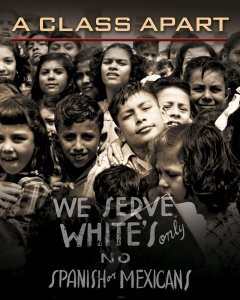

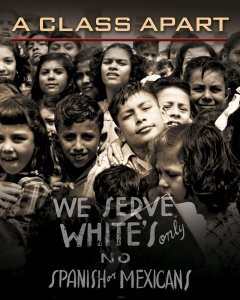

Award-winning producers, Carlos Sandoval and Peter Miller took a four-year journey into the past to make the documentary, A Class Apart which will air on PBS American Experience, Monday, February 23, 9 p.m. (Check PBS American Experience for local listings and Camino Bluff to organize your own viewing party the night of the show.)

Over the phone I talked with Carlos and Peter about going back in time to a place when Mexican Americans were categorized under “white”, and yet were not allowed to attend the same schools or serve on juries as their Anglo neighbors. They spoke about the challenges of telling the story of an invisible, yet courageous people and the full-circle journey of the case.

Chica Lit: When did you begin making A Class Apart?

Photo: Gustavo García, Pete Hernández and John J. Herrera at the Jackson County, Texas, Courthouse. Courtesy of Dr. Hector P. Garcia Papers/ Texas A&M University.

Photo: Gustavo García, Pete Hernández and John J. Herrera at the Jackson County, Texas, Courthouse. Courtesy of Dr. Hector P. Garcia Papers/ Texas A&M University.

Sandoval: There are three parts to that question. The very first filming that I did was at a conference on the case at the University of Houston in November 2004. I hired a local crew and interviewed people, including James Miranda, the original lawyer on the case who died about a year and a half ago. I used some of those interviews to put together our sample reel to seek additional funds. In May 2006, we really began the bulk of filming in Edna and the question became how do we find the people who knew about the case and also come up with archival material to be able to tell the story? We were very lucky because we did get the nephew of Pete Hernández and Victor Rodriguez who knew Pete and was there when the murder took place. It was guerrilla research that went on there.

Then it [became] about trying to find a partner on project.

Miller: It was at a party of filmmakers where I met [Sandoval]. He was telling me about this project and that he was looking to work with this with people who’ve done this before and I said, ‘How about me?’

I know a lot about history but never heard about the early Mexican American civil rights history and I thought, I should know about this. My passion and interest are in stories of people whose stories have been marginalized, or not been told. The telling of history is critically important in questions of justice. If the history of a people is legitimized, if it is told, it is an important part of achieving rights and standing in society.

The Hernández case has no transcript at the Supreme Court … nothing was written down on what was said on the day of the argument, no tape recording. There were no photos taken of lawyers in Washington; there were very few photos of anyone involved in the case. We had to piece together what happened in the Supreme Court that day with little scraps of information of what was an incredibly dramatic event that happened. At base of our story is invisibility; a community that’s invisible in eyes of Americans.

Chica Lit: Could you give us some historical background of the case?

Sandoval: [Pete Hernández] is no Rosa Parks. It’s not an easy civil rights case. This is a person who did in fact kill another man and there were consequences to that. The lawyers [Garcia and Cadena] were brilliant in realizing [the case] presented an opportunity despite the nature of the case to try to move forward on the constitutional rights of Mexican Americans. School segregation was on the way out; Mendez v. Westminster provided a precedent to desegregate schools in Texas. They were able to take out housing segregation.

But jury discrimination in Texas remained. At the that time, the Supreme Court already declared that you couldn’t discriminate jury selections with African Americans. The way Texas got away with it was that Texas said Mexican Americans were white, as long as there were whites on a jury you are tried by a jury of your peers. We were white when it was convenient for the state of Texas and that’s where the lawyers were very clever. [They argued] we may be white within the category of white but we’re treated as a class apart. That’s the argument that won the Supreme Court.

Chica Lit: What surprises did you find along the way?

Sandoval: The moment for me was when we were in Edna and we were told about a segregated cemetery. It remained on a de facto basis segregated. When we went to film, I was walking down a gully that divided the Latino community from the Anglo community. That for me was the most visible remaining symbol of the Jim Crow-like segregation that took place at that time and realizing that my parents or grandparents could’ve faced it, or I could’ve faced it.

Sandoval: The moment for me was when we were in Edna and we were told about a segregated cemetery. It remained on a de facto basis segregated. When we went to film, I was walking down a gully that divided the Latino community from the Anglo community. That for me was the most visible remaining symbol of the Jim Crow-like segregation that took place at that time and realizing that my parents or grandparents could’ve faced it, or I could’ve faced it.

Miller: We were having breakfast at this diner and talking to a waitress there about the case and the film. She said, ‘oh that’s really interesting’ and started telling us that there were still problems with the police and discrimination getting jobs. We asked, ‘Can we talk to you’ and she said said, ‘I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t live in this town if I talked about those things.’

Fifty years [after the case], we’re talking to people in the same town who don’t want to talk about discrimination around them because they’re afraid of the repercussions.

Paulina Rosa testified in the trail to establish the pattern of discrimination in order to prove jury discrimination. [Her child, who was an American citizen, could not attend the white public school.] To me, making these movies is about meeting the folks who dealt with that stuff. It’s one thing to talk to the leaders or great orators who argued before the Supreme Court. But to talk to the mother who lived in a tiny town where they’d kill you at night if you’re out – for [Rosa] to get up and do that – meeting people like her makes this work worthwhile.

Chica Lit: How have audiences reacted to A Class Apart?

Sandoval: I’ve been touring with the movie in Texas for about a week. The response has been overwhelming. It’s almost, with some of these screenings and Q&A’s, a revival meeting because people are bearing witness to the discrimination they personally experienced. Or we hear, ‘my abuelo or abuelita told me about this and I didn’t realize this existed or how bad it was.’

Sandoval: I’ve been touring with the movie in Texas for about a week. The response has been overwhelming. It’s almost, with some of these screenings and Q&A’s, a revival meeting because people are bearing witness to the discrimination they personally experienced. Or we hear, ‘my abuelo or abuelita told me about this and I didn’t realize this existed or how bad it was.’

Last week, the Texas state legislature read a proclamation about the film. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied [Hernandez] the 14th Amendment. That court is in the same building where the proclamation was read.

A Class Apart will air Monday, February 23rd at 9 p.m. on PBS. Check your local listings at www.pbs.org/americanexperience, and then plan a viewing party with your friends, classmates and family at Camino Bluff Productions.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-H4qhahKFKU&hl=en&fs=1]